High Plains Gardening

The gardening website of the Texas High Plains Region

Pollinator Friendly Gardens

Pollinator Friendly GardensThe buzz is missing in the garden; a “silent spring” summer and fall has descended across our nation's home landscapes. Even in wild areas, the sound of buzzing bees and other pollinators has diminished.

The past number of years, one of the hottest gardening trends is to plant a pollinator-friendly garden, for hummingbirds, butterflies and too a lesser extent, for bees. A short century ago, this never would have happened, as gardens naturally attracted pollinators and pollinators were all around. Remember when the kitchen garden included room for cut flowers and herbs, and some of the crop would be allowed to flower and go to seed?– all pollinator-friendly plants.

The news of pollinator shortages has been alarming, attracting national attention in the past. Those efforts are not enough. The news today is even more dire. According to the just released (February 26, 2016) pollinator assessment by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity Ecosystems (IPBES), entitled Thematic Assessment of Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production, 16% of vertebrate pollinators (increasing to 30% for island species) and more than 40% of invertebrate pollinating species are threatened locally, across the globe. It has been said many times, that art, literature, design, and politics are shaped by our culture. America's ubiquitous lawn is one example. So are garden and landscape design shaped by our current culture of over use of exotic species, exclusion of native plants, overuse of pesticides, and over tidying garden clean-up practices.

Gardening and agriculture has swung so far to the side of control of nature that we are on course to obliterate it. Over the centuries of plant exploration, gardeners world wide have so clamored for the new and exotic, that native local plants are no longer to be found in home landscapes. Most home gardeners are hard pressed to name even five native plants, let alone, three they grow in their gardens. Home gardeners enjoy exotic ornamentals not just for their novelty and utility, but because many of them have no predators, displaying little insect damage. Many exotic plants (that is, non-native plants) also provide little nectar, pollen or habitat for native pollinators.

To compound the problem facing pollinators – bees, flies, moths, butterflies, wasps, beetles, bats and birds – many of the plants, particularly summer annuals, have had the pollen and nectar  hybridized out of them to either a partial or a complete degree. As with most cultural changes, this occurred slowly, over the past hundred years. Sometimes it takes a problem so potentially catastrophic as the Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and the monarch butterfly decline to flash an urgent warning that gardening and agriculture has gone too far to the extreme end of control.

hybridized out of them to either a partial or a complete degree. As with most cultural changes, this occurred slowly, over the past hundred years. Sometimes it takes a problem so potentially catastrophic as the Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and the monarch butterfly decline to flash an urgent warning that gardening and agriculture has gone too far to the extreme end of control.

Pollination is the wonderful story of plants and animals working together to form a functioning global ecology. As much as we don't like insects, they are essential to life on Earth, as we've known it. We may not like them within our homes, but the cultivation of an appreciation for them in the garden is essential. The vast majority of insects are beneficial insects. Not all beneficial insects are pollinators, however, they perform roles that are essential to the cycle of life.

It is estimated that there are approximately 200,000 animal species that pollinate. Roughly 1000 of these are vertebrate animals such as humans, small mammals, birds, and bats. The majority are invertebrates -- bees, flies, butterflies, moths, wasps and beetles that pollinate more than 75% of flowering species of plants. The latest figures from the pollinator assessment states that between $235 billion and $577 billion (U.S. dollars) worth of annual global food production relies directly on pollinators.

The scope of this article on pollinator-friendly gardens is limited to the invertebrate pollinators, insects that are beneficial. Pollinators are a keystone species group, also referred to as indicator species that mirror the health or ill-health of an ecosystem. In the United States, the monarch butterfly is consider an individual indicator species, as is the European honeybee, because of its importance to agriculture.

The flowering plants that require pollination includes plants we humans use as food, spices, beverages, medicines, and fibers. One third of our global food supply depends on insects for pollination, including apples, oranges, melons, blueberries, strawberries, beans, cashews, carrots, broccoli, almonds, pumpkins, canola oil, coffee and chocolate, to name a few (list of crops and their pollinators in Wikipedia). Over 100 agriculture food crops grown in the U.S. and Canada require insect pollination, mainly from bees, and usually from the non-native European honeybee, Apies mellifera. If we think of it in terms of one out of every three bites of food we take are directly a result of a pollinator, we can appreciate them better.

The flowering plants that require pollination includes plants we humans use as food, spices, beverages, medicines, and fibers. One third of our global food supply depends on insects for pollination, including apples, oranges, melons, blueberries, strawberries, beans, cashews, carrots, broccoli, almonds, pumpkins, canola oil, coffee and chocolate, to name a few (list of crops and their pollinators in Wikipedia). Over 100 agriculture food crops grown in the U.S. and Canada require insect pollination, mainly from bees, and usually from the non-native European honeybee, Apies mellifera. If we think of it in terms of one out of every three bites of food we take are directly a result of a pollinator, we can appreciate them better.

Closer to home, in the arid U.S. Southwest, nearly all of the bushes and smaller trees are pollinated by local native bees. Without the bees, these flowering plants would keep growing and flowering each year, just not reproducing. And gradually over time, there would be less and less plants. Of course, this is already happening, with species becoming extinct.

No one pollinator pollinates every plant. Bees are the insects that pollinate most flowers. Some plants can be pollinated by numerous different pollinators, whether they are different species of bees, or pollinated by various species of bees, butterfly, flies and beetles. Any particular pollinator may not be able to pollinate a flower during its bloom cycle, so other pollinators step in. A pollinator may be able to pollinate many or all plants within a plant family, such as all species of goldenrod (Solidago) for example. Other plants are called “species specific” to just one, or maybe a few species of pollinators. The life cycles of pollinators are often in sync to the life cycle of their host plants.

Pollinator Problems

The amplified problems facing European honeybees are problems facing other pollinators. A number of human activities have contributed to the problem of diminished pollinator populations. Increased and persistent herbicide and pesticide use is a factor along with global climate change, which disrupts the timing of the life cycle of flower and pollinator.

The amplified problems facing European honeybees are problems facing other pollinators. A number of human activities have contributed to the problem of diminished pollinator populations. Increased and persistent herbicide and pesticide use is a factor along with global climate change, which disrupts the timing of the life cycle of flower and pollinator.

Fragmentation, degradation, and loss of habitat and habitat diversity used by pollinators is a major contributor to pollinator decline. Plant diversity is closely related to pollinator diversity. Agriculture, urban development and invasive species are some of the factors that lead to a decrease in habitat and habitat diversity. Light pollution for street and building lights unfavorably impacts populations of nocturnal insects, particularly moths.

Even non-native honeybees will out-compete native bees in accessing local nectar and pollen sources. An example of being out-competed is the yellow banded bumblebee native in Wisconsin. The yellow banded bumblebee was the most abundant bumblebee in Wisconsin, now it makes up less than 1 percent of the bumblebee population. I have fond memories of stepping of these bees and being stung as a child. Today, such a rite of passage is rare among the unshod. It is suspected that commercially raised bees that are diseased (weakened by mites, pesticides and lack of diversity) may be able to pass on their diseases to native bees.

Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation has red-listed 59 species of butterflies and moths and 57 species of bees. These are the pollinators identified as at greatest risk that covers the range from vulnerable, imperiled, critically imperiled populations to almost extinct. Additionally, the World Conservation Union has listed 2 bat and 13 bird species as endangered U.S. pollinator species. These numbers were before this past's month's pollinator assessment.

Bees We have more data on native and non-native bees than other pollinators; they are the most studied of our pollinators. Although a lot of attention is given to the easily transportable European  honeybee, North America is home to approximately 4000 species of native bees (20,000 bee species globally), pollinating approximately $3 billion out of $20 billion total estimated crop values in 2000. This total does not include indirect products like milk and beef produced through alfalfa pollination.

honeybee, North America is home to approximately 4000 species of native bees (20,000 bee species globally), pollinating approximately $3 billion out of $20 billion total estimated crop values in 2000. This total does not include indirect products like milk and beef produced through alfalfa pollination.

Native bees are all around us, or should be. Instead of a social lifestyle living in colonies like the honeybees and bumble bees (Bombus ssp.), 90% of bees are solitary bees. In addition to being classified as social or solitary bees, bees are either generalists, gathering food from a wide range of flowers, or specialists, servicing only a singe plant family or genus.

Native bees do a really good job of pollination. After all, before the introduction of European honey bees, native bees pollinated plants and agriculture crops in North America just fine. The introduction of hundreds of acres planted in one type of fruit tree or crop coming into bloom at once necessitated an infusion of hundreds of thousands more bees. Thus, the commercial European honeybee hive pollination service began.

Growers are looking into old-new methods of pollination to augment pollination by commercial hives. Smaller growers are planting hedgerows and flower strips among their orchards and fields to attract and nurture native bees. Studies have shown that when native bees pollinate orchards, they are more productive, as in hours on the job, and in crop yield. Native bees begin pollinating earlier in the morning and continue later in the day and in wet, cloudy or cool conditions February through November in most climates than honeybees. In the past, native bees met all the farmer's pollination needs. It is dangerous to be so dependent on just one pollinator species, the European honeybee. Any improvements that are made in commercial honey bee culture and life cycle will positively affect other pollinators.

Home gardeners might not even see many native bees doing their job. They range in size from very tiny 1/12th of an inch to more than an inch in length, many looking unbee-like as flying ants and flies. Native bees can be out and about nearly anytime of the year. On many days during our Texas Panhandle winters, tiny low lying flowers will open and be visited by tiny bees. The invasive non-native (and edible) purple flowering henbit is a source of nectar and pollen for bees.

Native bees include carder and cutter bees, carpenter and plasterer bees, leafcutter and mason bees, digger and sweat bees, and the bumble bee noted for its pleasant buzz. Most of the time one wouldn't notice their nesting places. They nest in the ground in narrow tunnels consisting of a few brood cells or in small cavities stocked with pollen and nectar, building their nests with bits of plant matter they forage. The adult female dies after building and stocking her nest and laying her eggs. The offspring remain in the nest, growing through the egg, larvae and pupa stages before emerging as an adult to begin the cycle again; the length of the life cycle varies from species to species.

Native bees include carder and cutter bees, carpenter and plasterer bees, leafcutter and mason bees, digger and sweat bees, and the bumble bee noted for its pleasant buzz. Most of the time one wouldn't notice their nesting places. They nest in the ground in narrow tunnels consisting of a few brood cells or in small cavities stocked with pollen and nectar, building their nests with bits of plant matter they forage. The adult female dies after building and stocking her nest and laying her eggs. The offspring remain in the nest, growing through the egg, larvae and pupa stages before emerging as an adult to begin the cycle again; the length of the life cycle varies from species to species.

Within these broad classifications of bees, are many variables. For instance, among the solitary bees that nest underground, many may share a common tunnel, each digging their own brood space and cells. I found one of these tunnels one summer afternoon after I noticed bee after bee circling, then disappearing down the entrance. Nearly a third of solitary bee species nest in abandoned beetle burrows. The other 70% nest in the ground, digging tunnels in bare or sparsely vegetated soils.

Other solitary bees nest in pre-existing holes made by beetle larvae or in the center of pithy twigs. Plants with stems frequently used by tunnel-nesting bees are box elder, agave, sunflowers, sumac, wild rose, raspberry, blackberry, elderberry, cup plant, snowberry, ironweed and yucca. Old canes, stems and stalks are burrowed into for their nest. Overzealous pruning and cleaning of landscape beds removes potential nest sites. Making bee hotels are beneficial. Click here for instructions and information on making and maintaining bee houses.

Bees forage for nest building materials. If you've grown roses, no doubt you've seen the half moon cut-outs on the leaves, cut out by specific species of leafcutter bees (Megachilidae). Some native bees are only found where their native forage materials usually grow, as in the leafcutters that prefer the leaves of the cranberry bush, or the leaves of red maples trees in northern and north eastern areas of the U.S.

Each type of bee has their own type of nest and life cycle. I found leafcutter bees making nests for their larvae in the water spout of my fountain. Nearly every time I wanted to run the fountain, the spout would be jammed with leaf bits and larvae down the length of the spout. Cleaning it out required inserting a long wire back and forth until the flow of water could wash the rest out. This was annoying not only because it was time consuming, but I knew I was destroying its larvae and nest.

Bumble bees are larger and therefore can be more aggressive within flowers to acquire pollen and nectar. They prefer nesting in old rodent holes, in brush piles and in stumps. Bumble bees store very little pollen and nectar in their nests, and therefore need to forage daily. The importance of food and nest forage materials for natives bees cannot be overestimated.

Bumble bees are larger and therefore can be more aggressive within flowers to acquire pollen and nectar. They prefer nesting in old rodent holes, in brush piles and in stumps. Bumble bees store very little pollen and nectar in their nests, and therefore need to forage daily. The importance of food and nest forage materials for natives bees cannot be overestimated.

The shape of the individual bee species dictates which flowers it will visit. Short-tongued bees visit asters or daisies, long-tongued bees can reach nectar in penstemon, lobelia and lupines. The size of the bee makes a difference in its range too. Large bees like the bumble bees can forage up to a mile away from its nest, medium sized bees, such as the miners and leafcutters can travel up to 400-500 yards, smaller sweat and carpenter bees generally only go up to 200 yards away, and the tiniest bees maybe only a 100 yards.

Many plants native to the Southwest are excellent pollinator plants. As mentioned above, most trees and shrubs are pollinated by bees, as are many cactus flowers, most members of the Asteraceae or Compositae (aster or sunflower family), desert zinnia, desert marigold, paperflower, and many members of the nightshade family, which includes tomatoes, eggplants, and potatoes. Mediterranean culinary herbs are pollinated by bees, and make excellent additions to a pollinator garden.

Wasps are not major pollinators, providing incidental pollination. Wasps are mainly observed on shallow flowers such as members of the carrot family and goldenrod, with easily accessible nectar to their short tongues. Pollen wasps have longer mouth parts than other wasps and gather pollen and nectar for their young. These pollen wasps prefer flowers primarily from the Waterleaf (Phacelias are the most common) and Figwort (Penstemons, monkey flowers, Indian Paintbrush, Verbascums, Veronica) families. Tarantula hawk wasps have been found feeding on milkweeds and creosote flowers.

Flies Our mental image of flies as a group is usually the pesky housefly and the nasty bites from the female horsefly. Flies are not nearly as attractive to people, or gardeners, as butterflies or bees, nor are gardens designed with the fly in mind, as I could fine no examples of gardens dedicated to flies. However, a garden planted for pollinators will also welcome the myriad species of beneficial flies. If for no other reason, we should like flies as pollinators, as we wouldn't have chocolate without them.

nor are gardens designed with the fly in mind, as I could fine no examples of gardens dedicated to flies. However, a garden planted for pollinators will also welcome the myriad species of beneficial flies. If for no other reason, we should like flies as pollinators, as we wouldn't have chocolate without them.

There are 120,000 species of flies in 188 families, of which flies from 71 families have been observed visiting flowers. A study on fly pollination cited that 555 plant species have been observed regularly pollinated by or visited by flies and are “pollinators of over 100 cultivated plants including cacao, mango, cashew, tea, and onions”. Other studies have noted flies pollinating and/or visiting more than 1100 plant species. Flies are second in importance as pollinators, but not as important or efficient as bees, however, “flower flies (Syrphidae) can be the most effective pollinators producing the highest seed set (Kühn et al. 2006). There are far fewer studies of flies as pollinators than bees.

If you watch flowers of native plants closely, it won't take long before you notice the amazing amount of fly activity around the blossoms. Many of the flies look like bees, rather than the housefly image we have of them. The main fly pollinators are the flower flies (hover and syrphid flies), bee flies (often looking like bumblebees), small-headed flies, house flies and tachinid.

Flies that visit flowers have short mouth parts that limit them to shallow, flat flowers. In the case of bee flies, their mouth parts are longer than other flies, though shorter than actual bees. Flies are known to pollinate strawberries and onions, apples and many other fruit trees, orchids, peppers, fennel, coriander, caraway, parsley, members of the carrot family, roughleaf dogwood, leadplant, winecups, black samson echinacea, many cactus flowers, blazing star, goldenrod, and ironweed. In alpine regions (photo at right taken in the alpine tundra of the Rocky Mountains), and in the Arctic, flies are the more frequent, therefore, more important, pollinators.

Fly studies as pollinators are few and infrequent. There is no documented evidence of a decrease in fly populations in the U.S., however, there are no studies about it either. A study done in Poland discovered a significant decline in “syrphid flies within urban and agricultural areas, as compared to species rich natural habitat.” One fly is listed as endangered on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service endangered species list.

Butterflies and moths, rank third in importance as pollinators under bees and flies, but are far more beloved. Butterflies are not pesky (although moths can be), are colorful, beautiful and graceful. There are over 12,000 species of moths and butterflies in North America; only 800 butterfly species live north of Mexico. Butterflies and moths, the “flowers of the air” as E. O. Wilson has called them, are mainly accidental pollinators. But that doesn't stop us from adoring butterflies and composing gardens to attract them. As a consequence, the practices of gardening that nurture butterflies, nurtures other pollinators. Likewise, when following the practices of gardening for bees, all other pollinators, including our beloved butterflies, will benefit.

Butterflies are mainly specialists, requiring specific plants or plant families for completion of their life cycle. Butterflies prefer colorful, fragrant flowers with flat and broad surfaces on which to land and sip nectar. Common garden plants for butterflies include asters, goldenrods, butterfly weed, butterfly bush, milkweed, ironweed, coneflower, dogbane, dahlias, marigolds, zinnias, fleabane, thistle, senna, lantana, blue mist flower, peony, lupine, vetch, yarrow, phlox and others. Many butterflies require specific host plants for laying their eggs, such as the milkweed (Asclepias spp.) for monarch and other butterflies. Monarchs migrate to overwinter, but many species hibernate in place – in hibernation sites of leaf litter, loose bark, branch and log piles are available. Excessive fall clean-up eliminates many hibernation sites.

Some host plants for caterpillars are various milkweeds, trees, shrubs, grasses, evening primrose, passionflowers, tomatoes, and yellow flowering sennas to name a few.

Moth habitats are similar to butterflies, however, moth-pollinated flowers are quite different. Moths are mostly nocturnal, visiting flowers that open at dusk that are white or pale in color with a heavy-sweet fragrance. Desert four o'clocks, datura, moonvine, yucca flower, and calylophus are flowers pollinated by moths. The hawkmoth we frequently see here in the Texas Panhandle is the white-lined sphinx moth, Hyles lineata.

To garden for specific butterflies and moths, the best online source is the Butterflies and Moths of North America site, which is searchable down to individual counties. For Randall County, Texas, click here. Then click on any of the butterflies to see images and information about habitat as a caterpillar and adult and its food requirements.

Beetles Fossil records indicate that beetles were probably the first insect pollinators of prehistoric flowering plants. Beetles pollinate 88% of the 240,000 known flowering species. It is unknown how many of the 340,000 beetle species are species that pollinate flowers. Generally speaking, pale, white and green flowers that emit strong volatiles like magnolias, water lilies, asters, sunflowers, coneflowers, goldenrod, sweetshrub, spicebush, rose, spirea, paw paws are some of the flowers pollinated by beetles. Some of the more common types of pollinator beetles in North America are soldier beetles, long-horned beetles, jewel beetles, blister beetles, scarabs, soft-winged beetles, checkered beetles, tumbling flower beetles and sap beetles. Beetles burrow into twigs, stems, branches, bark, and trunks of dying, decaying and dead wood as well as rotting organic matter to lay eggs. Beetle pollination is more prominent in the tropics than in temperate zones.

Leaving leaf and other plant matter to decompose will provide habitat for beneficial beetles.

Home gardeners can most positively and directly affect the problem of pollinator shortages through a different gardening paradigm than is currently being practiced in home landscapes. The recent global pollinator assessment listed specific options to encourage pollinator life for home landscapes, agriculture and government entities.

Chiefly, for the home gardener, these include:

Reducing the amount of turf and replacing it with a diversity of plants will attract pollinators. Decreasing the number of non-native exotic ornamentals in the landscape by replacing them with plants native to the region and decreasing or eliminating the use of herbicides and pesticides are important steps. Results can be achieved in one's home landscape within one growing season. Pollinator gardens include the basics of food, water and shelter, including habitat for over-wintering. Even when one's landscape is surrounded by other residential turf gardens that use herbicides and pesticides, one can bring back beneficial native pollinators into your home landscape. I know its possible, I've done it.

Planting pollinator-friendly gardens involves a few key principles:

Choose Pollinator Plants The basic idea in creating pollinator friendly gardens is to provide food and habitat for pollinators throughout the year. Because there are so many possible pollinators and plants, it's really quite easy, especially when planting with native plants. However, any pollinator garden doesn't have to be exclusively native, as many heirloom, non-hybridized exotic plants can provide pollen and nectar to pollinators that are generalists. Any exotic plant that requires one specific pollinator won't be pollinated unless that pollinator is present (or unless the function is provided by the gardener), but it may still be able to provide pollen and nectar.

As your garden increases in plant diversity, the diversity of pollinators will naturally increase. For home gardeners who desire to hear the buzz of bees and see the beauty of butterflies and grow food that requires invertebrate pollination, a garden in harmony with nature is the natural path to success.

Pollinator-friendly plants can be planted as room is available in garden beds and border, following the guidelines below. Observe which plants to keep to see if they are visited by pollinators. A garden makeover doesn't need to be completed in one year; take it in stages. Choose a sunny area that would work best to begin the conversion, then as the years go by, add more and more area for plants that are useful to pollinators. Make every plant count through research and grouping them together.

Include flowers that are attractive to both your self and the pollinator in a host of colors, blooming late winter, spring, summer and into late fall providing a continual source of food. Flowers and plants that are heirloom or native will have sufficient pollen and nectar. Not all cultivars are pollinator-friendly – cultivars and hybrids may not offer the same amount of “pollen and nectar rewards” as straight species.

Plant at least three different species to be in bloom at one time, in clumps of at least 3 feet square for best results in attracting pollinators. Massing of plants in large enough groupings will attract their attention through the volatiles they emit, and their color coding. In small gardens, plant single species together, rather than in small isolated clumps. A diversity of flower shapes will attract a wider range of pollinators. Bee and butterfly diversity is maximized when 15-25 different flower species are present. Drifts of cultivars that do not attract pollinators, though colorful, are a waste of space in a pollinator-friendly garden. Plant borders of flowers near or around vegetable gardens to bring in beneficial insects, which will help combat predator insects. Summer annuals of cosmos, single-flowered marigolds (not doubles), sunflowers and zinnias are good examples. Flowers unnaturally bred to bloom double confused the pollinators and often reduces the amount of nectar and pollen. During bloom times, observe whether the plants have pollinator activity and record the type of pollinator (bee, fly, butterfly, beetle, etc) for future reference.

Many native, and non-native, trees, grasses and shrubs are host plants for caterpillars. Design your garden areas using vertical spaces by choosing pollinator-friendly ground covers, herbaceous and woody perennials, shrubs, vines and trees.

Pollinators need the less manicured garden areas for resting, hiding, foraging, laying eggs, and rearing young. Avoid the pollinator-pitfall of excessive tiding up in the garden. Once pollinators are invited into your garden and lay eggs, allow them to overwinter for the following year. This is the important part of any pollinator garden. Minimal fall clean-up is advised. Or dedicate places in your garden out of public sight that are natural and desirable to pollinators.

Pollinators need the less manicured garden areas for resting, hiding, foraging, laying eggs, and rearing young. Avoid the pollinator-pitfall of excessive tiding up in the garden. Once pollinators are invited into your garden and lay eggs, allow them to overwinter for the following year. This is the important part of any pollinator garden. Minimal fall clean-up is advised. Or dedicate places in your garden out of public sight that are natural and desirable to pollinators.

Even in some managed habitats that feature plant diversity, our gardening practices interfere with the natural cycle of life. Prairie restitution projects manage plant species by burning and mowing practices. When entire areas are mowed or burned to benefit plant communities, pollinators find themselves homeless and hungry. New guidelines now take the ecology into account by recommending burning or mowing no more than a third of a site in a mosaic pattern at one time, allowing for re-colonization of pollinators as plants re-grow.

Windbreaks such as fences and buildings provide less windy areas. A water source such as a fountain, bird bath, pond, or a bowl of water beneath a dripping faucet is helpful and inviting to pollinators. Many pollinators need mud or mud puddles as well. Bees that nest underground need some bare spaces of soil.

Plants for Pollinators The list of plants that are pollinator-friendly is long – too long to try to re-create here. North America is blessed with many hundreds of garden worthy pollinator-friendly native plants, and our region is no exception. I've listed many resources below that feature plants that many different pollinators enjoy. Within the Plant Profiles here at HighPlainsGardening.com, one can search and filter plants by wildlife category, such as bees, butterflies and hummingbirds. The plant list for our own native plant nursery, Canyon's Edge Plants, also filters for pollinators (click here for example of bee plants). High Country Gardens catalog also is searchable by pollinators. The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center provides information about native flowers and their invertebrate partners. (Click here for the list of plants for native bees.) An additional reference is Selecting Plants for Pollinators, A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers and Gardeners, in the Southwest Plateau and Dry Steppe and Shrub Province, in parts of New Mexico and Texas, from the Pollinator Partnership.

Eliminate or Limit Pesticides and Herbicides Limit or eliminate pesticide, herbicide and fungicide use in the garden. When gardening in harmony with nature, these lethal “cides” are usually not necessary. Pesticide application guidelines that give information about using pesticides in the early morning or at night to avoid honeybees does not apply to native bees, as they are out and about early and later than honeybees. Don't over react to insect chew bites on leaves. Observe, assess, and evaluate the situation to see if interaction is warranted. (Review principles of Integrated Pest Management, IPM).

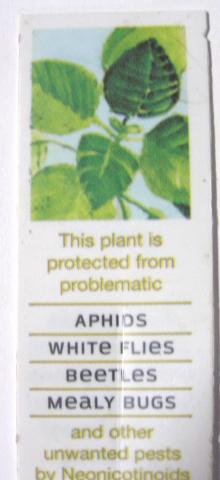

Avoid using systemic pesticides, the neonicotinoids. The neonicotinoid pesticides were introduced in agriculture as a “safer” alternative; their effectiveness is longer, therefore the frequency of spraying is decreased. However, many studies have shown that neonicotinoid pesticides severely impact pollinator populations, which includes butterflies.

Neonicotinoids are also used in home landscapes. Many of the Bayer group of home landscape insecticides contain neonicotinoids. Other neonicotinoid products are manufactured by Ortho, Fertilome, Green Light, Hi-Yield and others. For a list of commonly used products, click here. Products approved for use to homeowners can contain up to 32 times the amounts approved for agricultural use. (Monarch Joint Venture.) Also please note that organically approved pesticides can be harmful to bees. (Organic Approved Pesticides, Xerces Society).

Neonicotinoids are also used in home landscapes. Many of the Bayer group of home landscape insecticides contain neonicotinoids. Other neonicotinoid products are manufactured by Ortho, Fertilome, Green Light, Hi-Yield and others. For a list of commonly used products, click here. Products approved for use to homeowners can contain up to 32 times the amounts approved for agricultural use. (Monarch Joint Venture.) Also please note that organically approved pesticides can be harmful to bees. (Organic Approved Pesticides, Xerces Society).

Avoid buying plants that you know were treated with neonicotinoids. During the recent past, more and more nursery plants, including flowering nectar plants for butterflies and other pollinators, are sprayed and treated with neonicotinoid insecticides. Researchers from Friends of the Earth published Gardeners Beware 2014, a report exposing to the public that many bee-friendly plants (as well as vegetable plants, trees and shrubs) sold at big box stores, such as Home Depot, Lowes and Walmart, were treated with neonicotinoids at nurseries where these plants were grown. Home Depot finally took the step of informing its customers by having a tag inserted with each neonic-treated plant. This group of insecticides have a long lasting residual both throughout all parts of the plants, including flowers, pollen and nectar, and even in the soil. Yes, the pollen and nectar of these treated plants contain the neonicotinoid chemicals. Neonics can persist in soil and plants for months after application, even up to SIX YEARS in woody plants! (my emphasis). Neonic insecticides applied to your rose bush can affect nearby plants and soil. (Minnesota Public Radio.) Canyon's Edge Plants at 1401 5th Avenue in Canyon, TX supplies the area with neonic-free xeric, native and other great garden plants, including a host of nectar plants.

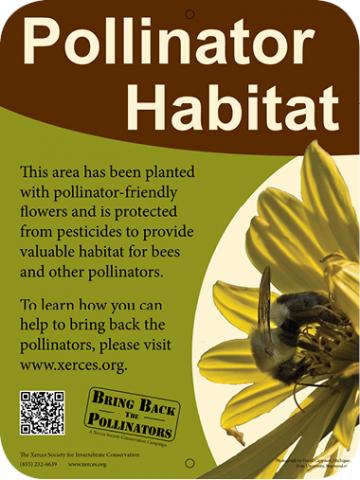

There are a number of organizations leading the way, united in a common goal of informing the public on factors related to pollinator decline, instructing home gardeners on pollinator-friendly practices, and promoting the increase in the number of landscapes and acreage that are hospitable to native pollinators (see resources below). The main group leading the way is the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Just one of their many outreach projects is public awareness. Xerces Society encourages gardeners to sign the pledge to protect pollinators. The pledge states:

“To Bring Back the Pollinators, I will:

1. Grow a variety of bee-friendly flowers that bloom from spring through fall.

2. Protect and provide bee nests and caterpillar host plants.

3. Avoid using pesticides, especially insecticides.

4. Talk to my neighbors about the importance of pollinators and their habitat.”

Home gardeners can spread awareness and help fund these campaigns by purchasing a Pollinator Habitat sign and/or a S.H.A.R.E. sign –Simply Have Areas Reserved for the Environment, from Pollinator Partnership. I've signed the pledge and registered my landscape with the Million Pollinators gardens under the HighPlainsGardening.com name in area code 79121. Gardeners and organizations with pollinator-friendly gardens can upload photos. Search their map of over 185,000 pollinator gardens here.

Do I think that home gardeners can save the 40% of invertebrate pollinators that are threatened today? No, I don't. This pollinator movement is moving too slow to save many pollinators already under threat. Homeowners are reluctant to make many changes,

Do I think that home gardeners can save the 40% of invertebrate pollinators that are threatened today? No, I don't. This pollinator movement is moving too slow to save many pollinators already under threat. Homeowners are reluctant to make many changes,  particularly, planting natives and reducing pesticide use. But we just might be able to act in time to save the next 10 or 20% of pollinators that will be threatened as current home and agricultural practices continue. Or if not them, then maybe the final 30% of pollinators in the next decade. With global warming heating up, disturbing the timing of flower and pollinator, humans must do their part and stop the demise of pollinators and pollinator habitats.

particularly, planting natives and reducing pesticide use. But we just might be able to act in time to save the next 10 or 20% of pollinators that will be threatened as current home and agricultural practices continue. Or if not them, then maybe the final 30% of pollinators in the next decade. With global warming heating up, disturbing the timing of flower and pollinator, humans must do their part and stop the demise of pollinators and pollinator habitats.

In the best tradition of Alexander von Humboldt, Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, E. O. Wilson is now calling for the Half Earth initiative: for us humans set aside 50% of the Earth's acreage, both land and sea, as a permanent preserve, undisturbed by man. After a life time of research and teaching about the environment (professor emeritus at Harvard University and winner of two Pulitzer prizes), at age 86, Dr. Wilson is publishing his 32nd book, Half Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life. In it he urges national leaders across the world to set aside wildlife corridors to prevent extinction of species. Is it too much to consider setting aside a percentage of one's home landscape to nurture our vital pollinators?

If lettuce and zinnias can be grown in space, then surely we can do our part, one gardener at a time. As home gardeners, the spot of land we can affect is the residential home landscape. Take and act on the Pollinator Pledge. Bees, butterflies and other beneficials will return and provide pleasant sounds and sights of summer as a consequence of performing their main job – keeping the planet humming smoothly.

I look forward to a time in the future when our view of gardening, nature and earth's ecology is such that we take it for granted again, that if we plant it, they will come.

Attracting Native Pollinators, Protecting North America's Bees and Butterflies, The Xerces Society Guide, Storey Publishing, 2011.

Beetle Pollination, USDA, US Forest Service.

Creating Organic Landscapes, HighPlainsGardening.com

Farming for Bees, Guidelines for Providing Native Bee Habitat on Farms, by Mace Vaughan, Jennifer Hopwood, Eric Lee-Mäder, Matthew Shepherd, Claire Kremen, Anne Stine, Scott Hoffman Black, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, 2015, revised.

Flies and Flowers, an Enduring Partnership, Kearns, Carol Ann, USFS Pollinator of the Month: Flies and Flowers Article, Xerces Society, January, 2008.

Flies – Pollinators on Two Wings, by Axel Ssymank, Bonn & Carol Kearns, Santa Clara, The New Diptera site.

Flower Flies, USDA, Forest Service, Matthew Shepherd and Scott Hoffman Black with contributions from Carol Kearns.

"How to Make and Manage a Bee Hotel: Instructions that Really Work", the Pollinator Garden, November, 2015.

In 'Half Earth', E. O. Wilson Calls for a Grant Retreat, Claudia Dreifus, New York Times, February 29, 2016.

Integrated Pest Management, HighPlainsGardening.com

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity Ecosystems (IPBES), entitled Thematic Assessment of Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, February 26, 2016.

List of Bee-Friendly Plants, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Provided by the Pollinator Program at The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

List of honey plants, by plant family, Wikipedia.

“North American Dipteran Pollinators: Assessing Their Value and Conservation Status”, Kearns, Carol Ann, University of Colorado at Boulder, 2001.Native Pollinators, NRCS, May, 2005.

North American Nectar sources for Honey Bees, Wikipedia.

Perilous Migration of the Monarch Butterfly, HighPlainsGardening.com, June, 2015.

Pocket Guide to the Native Bees of New Mexico, Grasswitz, Tessa and David Dreesen, New Mexico State University.

Pollinating Beetles of Texas, for a list with photos and their taxonomic name of pollinating beetles found in Texas.

Pollinator Partnership, Million Pollinator Garden Challenge initiative.

Power of Polllinators Module, University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems.

Selecting Plants for Pollinators, A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers and Gardeners, in the Southwest Plateau and Dry Steppe and Shrub Province, in parts of New Mexico and Texas, Pollinator Partnership™ (www.pollinator.org), in support of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC–www.nappc.org).

Texas Bee Watchers Bee Friendly Gardens, simple instructions for planting bee friendly gardens.

Angie Hanna, March 2, 2016